On January 15th, 2017, I made my way out to the front of the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building of the New York Public Library to attend a rally.

At about 10 minutes after the officially posted start time, a young girl that no one could really see started singing the national anthem in a clear strong voice. There was no MC, no announcement that the rally was officially starting, and there was a long silence while the first speaker made her way to the podium, which, the crowd noted shortly after, was too low on the steps. The volume of the microphones was also too low, and shouts of “louder!” came from the people furthest back.

It took a few readers — each coming up to the podium, saying their names and telling the crowd what they were reading– but finally someone pulled a microphone from a stand, asked the crowd if they were loud enough, and stood high enough up on the steps to get a huge roar of approval.

The empty podium, abandoned in the cold, became a symbol for the rally itself: when the people speak, its time for a change.

The PEN America sponsored Writers Resist rally was a solid two-and-half hours of authors, poets, and even politicians reading excerpts from Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, Maya Angelou, and of course, Martin Luther King Jr. — as well as many many others — in honor of Martin Luther King Jr. Day and in protest against an incoming presidential administration that regularly attacks the media and individual writers. Former United States poet laureates read inaugural poems from past administrations, and many other writers shared their own work, some written specifically for the occasion. There were readers and writers of every race, from myriad countries of birth, and from a multitude of backgrounds.

The themes of the readings were about fighting for freedom, standing up for democracy, and finding a place as a American when so many others might tell you that you don’t belong. Some people read song lyrics (a reading of Frank Zappa’s “It Can’t Happen Here” stands out), and others read parts of the constitution, including the First Amendment. The battle, the thing everyone was there to resist, was the silencing of words. Audre Lorde’s quote, made into a poster, was held above the crowd: “your silence will not protect you.”

The themes of the readings were about fighting for freedom, standing up for democracy, and finding a place as a American when so many others might tell you that you don’t belong. Some people read song lyrics (a reading of Frank Zappa’s “It Can’t Happen Here” stands out), and others read parts of the constitution, including the First Amendment. The battle, the thing everyone was there to resist, was the silencing of words. Audre Lorde’s quote, made into a poster, was held above the crowd: “your silence will not protect you.”

As a writer in the crowd slowly inching her way closer and closer to that empty podium and the readers standing several steps above it, I felt like I was getting a master class in the power of words. Even as the cold numbed my toes and fingers, and my feet ached from standing still for too long, my ears still caught carefully constructed lines, doing what precise prose and perfect poetry always does: inform, impress, and inspire.

While I found much of it moving, it was the inaugural poems that got me thinking. The first president to have an inaugural poem was John F. Kennedy.

“When power leads man to arrogance,” Kennedy is reported to have said, “poetry reminds him of his limitations. ”

When power narrows the area of man’s concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of his existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses.”

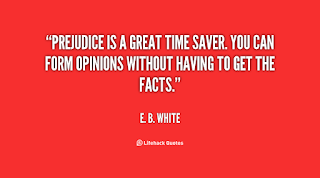

According to Wikipedia, only four other presidential inaugurations had poets prepare something for the occasion: Bill Clinton’s two inaugurations, and Barack Obama’s two inaugurations. That hasn’t stopped me, and indeed others, from imagining what poetry might inspire President-Elect Donald Trump. As I listened to speaker after speaker reading words about what it means to fight for freedom, I tried to imagine what sort of words Trump reads, what philosophers, what authors, what poets.

As the saying goes, “watch your thoughts; they become words. Watch your words; they become actions.” We are all shaped by what we read, the stories we take in, the ideas we absorb. More than the President-Elect’s tax returns, I want to see his reading list. I want to know what words will guide this new president; I fear the only words he cares about are his own, that he is a president without poetry.

I fear that he is a president that would rather censor the press than face criticism, that his attacks on the media are part of a greater attack on free speech. I fear that because he “knows all the words,” and “has the best words” he thinks he doesn’t need to listen, to read, and to learn.

So I gathered with hundreds of others in New York City (and hundreds more across the country) to listen to words, and to march to Trump Tower with a pledge to defend the First Amendment (signed by over 160,000 people) and to shout more words, as is my constitutional right. Peaceful protest (and not so peaceful) has been a part of every great change America has ever made. Our country was founded in protest of another country the people who made their way to our shores thought was unjust. The Founding Fathers wanted to create a space where democracy would thrive and understood that this could not happen if the very tools of the revolution they fought — including protest — weren’t protected. Every social revolution brings us ever closer to those ideals fought so hard for: a more perfect union with equality for all.

But not everyone has made the same study of those words, and many do not share the same vision for what equality looks like. As another saying goes: when you are accustomed to privilege, equality feels like oppression. For every person who wants to make America great again, there is another who is still trying to find a way to make it great for the first time, to find their place under the great umbrella of “for all.” For this second group of Americans, words of resistance — resistance to settling, to taking less, to living in despair — are what keep them going, keep them hoping, keep them dreaming.

And keep them reading, and keep them writing. Our very constitution is a poem to the ideals of freedom. This country was founded on the promise of words. I marched to help hold our country to that promise. And whenever I can, I will brave cold or heat and crowds and shouts to hear that promise spoken again and again.

Words have power. It’s why people in power fight so hard to silence them. And its also why writers will always be at the heart of every resistance.